Menu

4’33”

4’33”

17

17

18

18

19

19

5

5

4

4

3

3

7

7

11

11

1

1

22

22

26

26

29

29

21

21

15

15

17

18

19

5

4

3

7

11

1

22

26

29

21

15

In 1952, American composer John Cage walked onto the stage, sat down at the piano, lifted the keyboard lid – and played nothing.

For four minutes and thirty-three seconds he sat in silence, allowing the audience to hear everything else: coughing in the hall, rustling, the creak of chairs. Cage demonstrated that even in silence there is music – it is made up of the things we usually ignore.

When the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, a new chapter - the Story of an Independent Kazakhstan, began. Alongside it, popular music was born and transformed, reflecting eras, generations, and cultural shifts. Between 1991 and 2023 lie exactly 32 years. These are the years explored in the book 91-23: About Popular Music of Independent Kazakhstan (О populiarnoi muzyke nezavisimogo Kazakhstana). If each year were a single second, it would amount to 32 seconds of silence – the length of a pause in which the history of Kazakhstani music might have remained, had no one chosen to tell it.

91-23: About Popular Music of Independent Kazakhstan fills that silence – with voices, stories, and songs that defined entire generations.

In 1952, American composer John Cage walked onto the stage, sat down at the piano, lifted the keyboard lid – and played nothing.

For four minutes and thirty-three seconds he sat in silence, allowing the audience to hear everything else: coughing in the hall, rustling, the creak of chairs. Cage demonstrated that even in silence there is music – it is made up of the things we usually ignore.

When the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, a new chapter - the Story of an Independent Kazakhstan, began. Alongside it, popular music was born and transformed, reflecting eras, generations, and cultural shifts. Between 1991 and 2023 lie exactly 32 years. These are the years explored in the book 91-23: About Popular Music of Independent Kazakhstan (О populiarnoi muzyke nezavisimogo Kazakhstana). If each year were a single second, it would amount to 32 seconds of silence – the length of a pause in which the history of Kazakhstani music might have remained, had no one chosen to tell it.

91-23: About Popular Music of Independent Kazakhstan fills that silence – with voices, stories, and songs that defined entire generations.

In 1952, American composer John Cage walked onto the stage, sat down at the piano, lifted the keyboard lid – and played nothing.

For four minutes and thirty-three seconds he sat in silence, allowing the audience to hear everything else: coughing in the hall, rustling, the creak of chairs. Cage demonstrated that even in silence there is music – it is made up of the things we usually ignore.

When the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, a new chapter - the Story of an Independent Kazakhstan, began. Alongside it, popular music was born and transformed, reflecting eras, generations, and cultural shifts. Between 1991 and 2023 lie exactly 32 years. These are the years explored in the book 91-23: About Popular Music of Independent Kazakhstan (О populiarnoi muzyke nezavisimogo Kazakhstana). If each year were a single second, it would amount to 32 seconds of silence – the length of a pause in which the history of Kazakhstani music might have remained, had no one chosen to tell it.

91-23: About Popular Music of Independent Kazakhstan fills that silence – with voices, stories, and songs that defined entire generations.

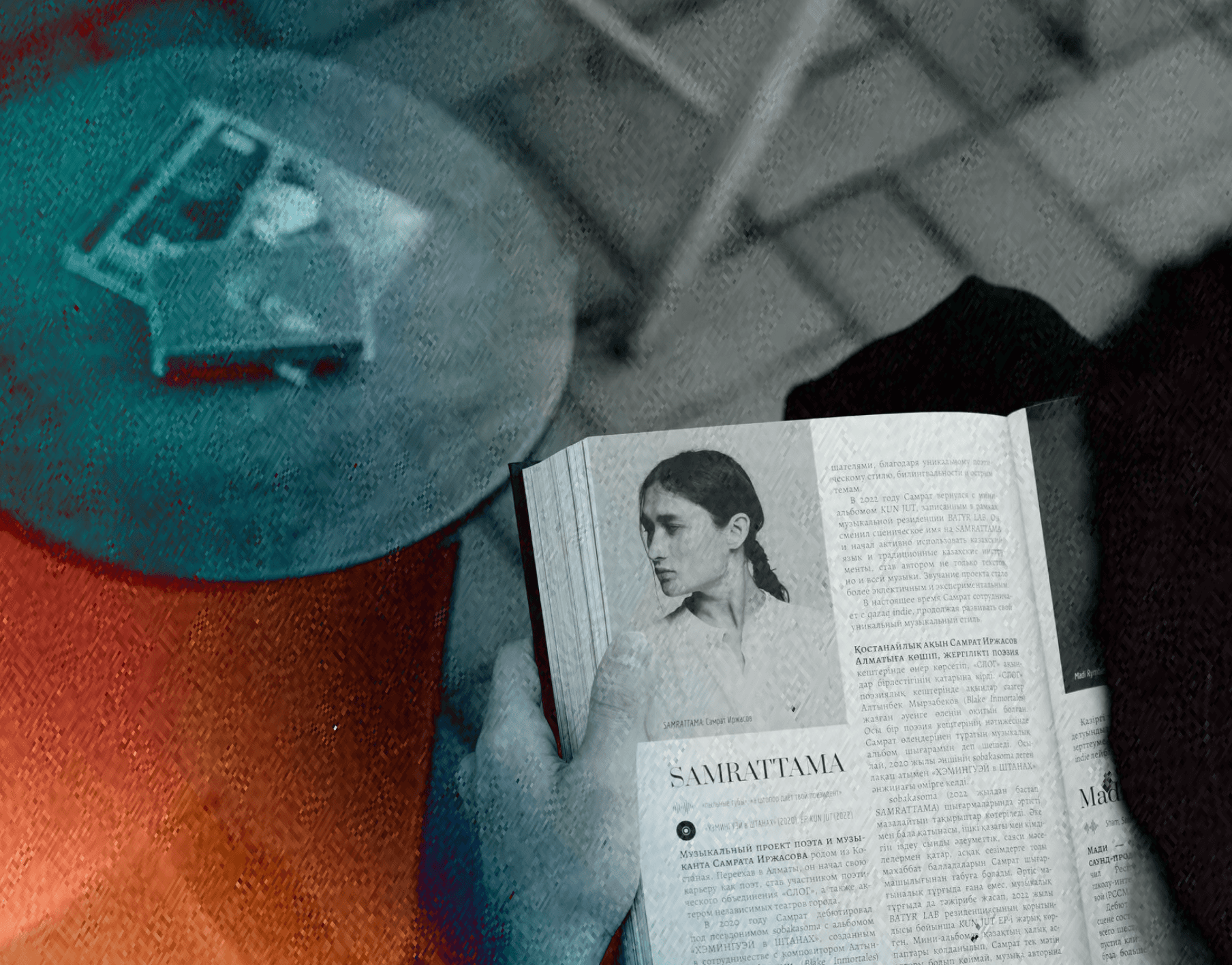

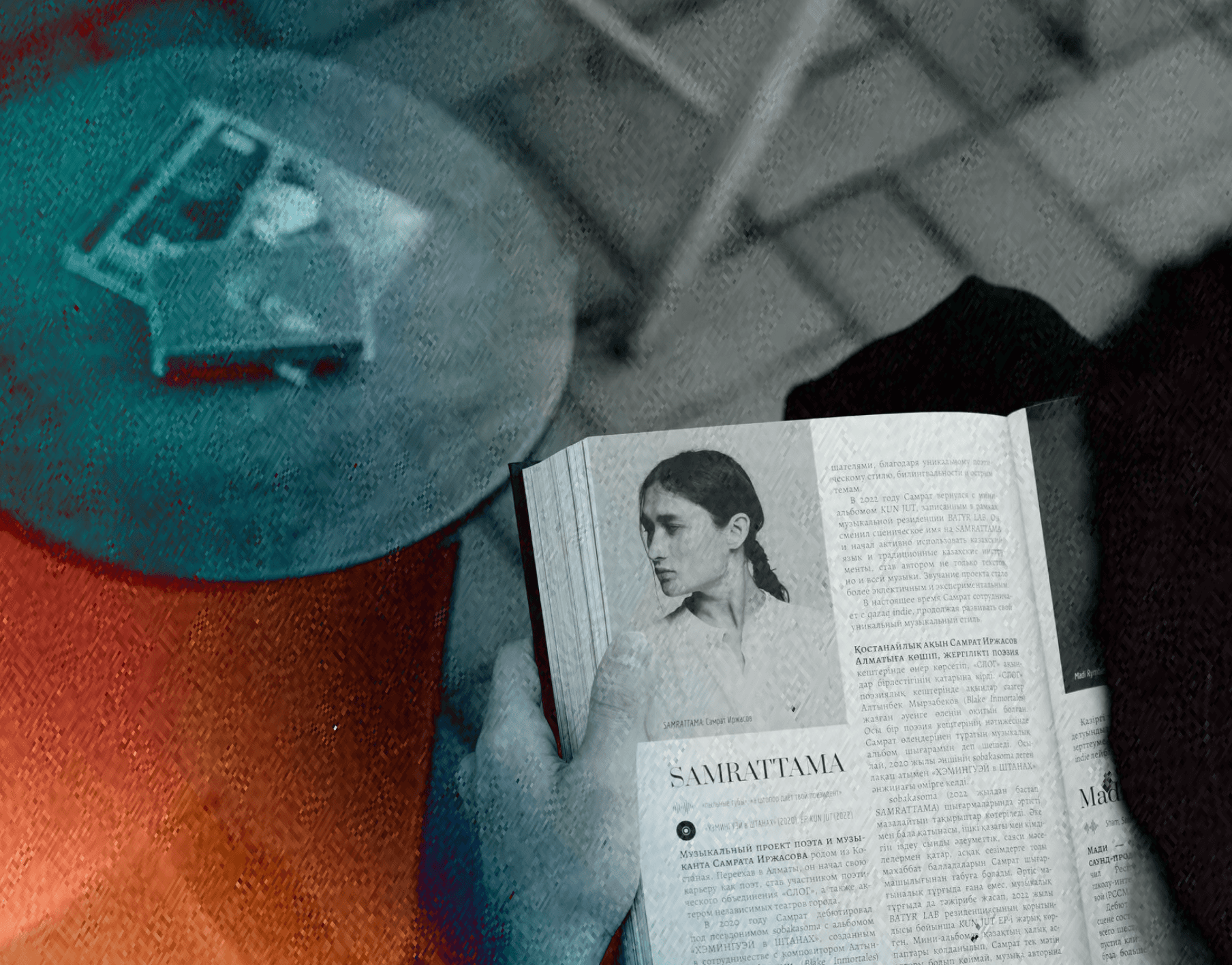

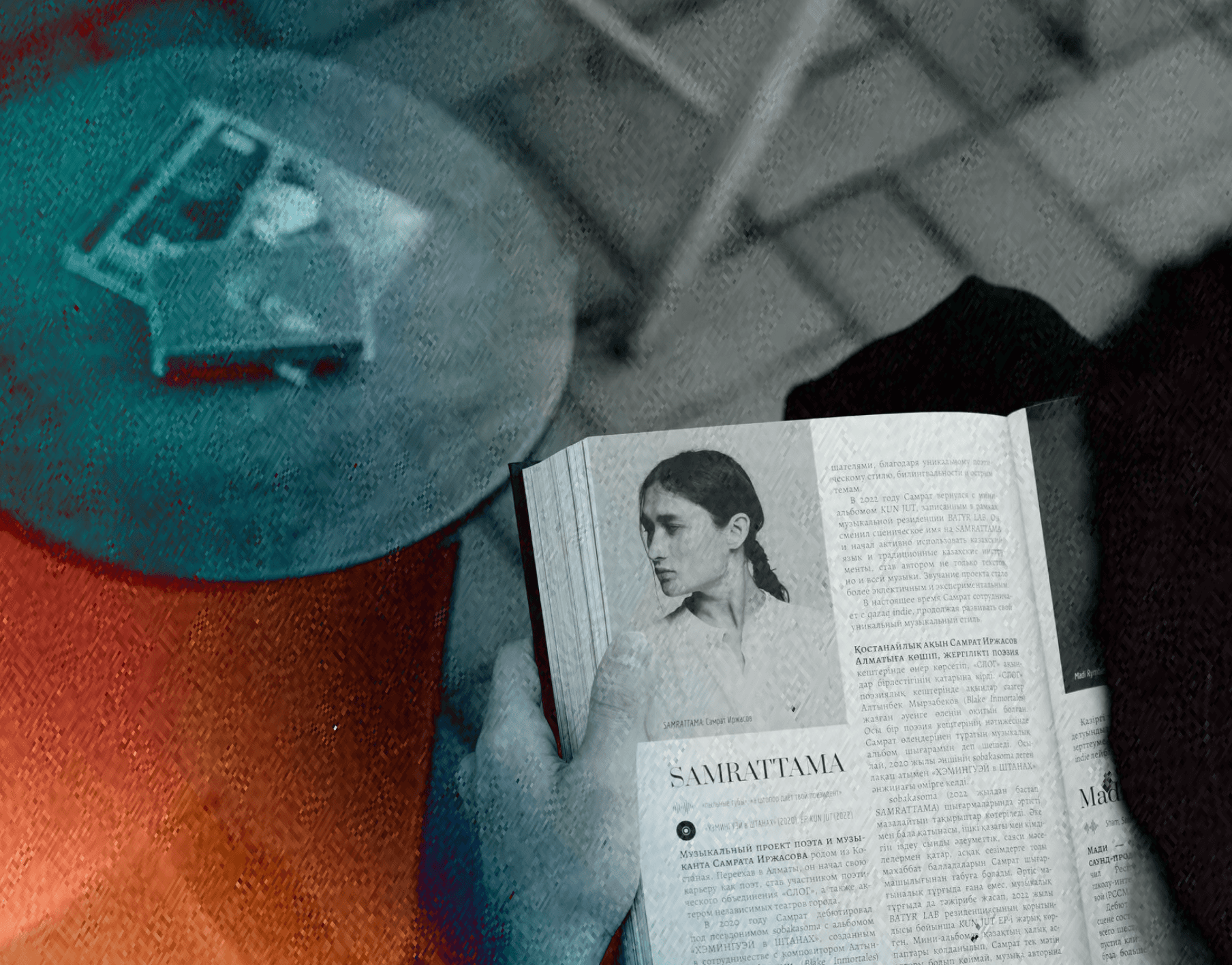

91-23: About Popular Music of Independent Kazakhstan is the first attempt to assemble a coherent picture of the local pop scene from 1991 to 2023. The book was created by the Batyr Foundation and is based on interviews, archival materials, and analytical research.

The book was presented on November 30, 2024; in March 2025 it was withdrawn from sale by court decision. The reason: a lawsuit alleging violation of personal non-property and exclusive rights related to the description of one of the artists featured in the book.

Now the authors must defend not only the text itself, but the very right to preserve cultural memory.

The initial amount claimed in the lawsuit was 195 million tenge – roughly equivalent to 4.5 years of work by the BATYR LAB residency, a program supporting young musicians, disseminating knowledge, and developing the music scene.

Eight months of legal proceedings demanded significant resources: the team’s time, legal support, and organizational effort.

The Foundation’s work did not stop, but some projects had to be scaled back or postponed, as attention and funding were redirected toward defending the book. At some point, instead of developing and supporting the music scene, the team was forced to spend its energy defending what had already been created – and the practice of independent research came under pressure.

91-23: About Popular Music of Independent Kazakhstan is the first attempt to assemble a coherent picture of the local pop scene from 1991 to 2023. The book was created by the Batyr Foundation and is based on interviews, archival materials, and analytical research.

The book was presented on November 30, 2024; in March 2025 it was withdrawn from sale by court decision. The reason: a lawsuit alleging violation of personal non-property and exclusive rights related to the description of one of the artists featured in the book.

Now the authors must defend not only the text itself, but the very right to preserve cultural memory.

The initial amount claimed in the lawsuit was 195 million tenge – roughly equivalent to 4.5 years of work by the BATYR LAB residency, a program supporting young musicians, disseminating knowledge, and developing the music scene.

Eight months of legal proceedings demanded significant resources: the team’s time, legal support, and organizational effort.

The Foundation’s work did not stop, but some projects had to be scaled back or postponed, as attention and funding were redirected toward defending the book. At some point, instead of developing and supporting the music scene, the team was forced to spend its energy defending what had already been created – and the practice of independent research came under pressure.

91-23: About Popular Music of Independent Kazakhstan is the first attempt to assemble a coherent picture of the local pop scene from 1991 to 2023. The book was created by the Batyr Foundation and is based on interviews, archival materials, and analytical research.

The book was presented on November 30, 2024; in March 2025 it was withdrawn from sale by court decision. The reason: a lawsuit alleging violation of personal non-property and exclusive rights related to the description of one of the artists featured in the book.

Now the authors must defend not only the text itself, but the very right to preserve cultural memory.

The initial amount claimed in the lawsuit was 195 million tenge – roughly equivalent to 4.5 years of work by the BATYR LAB residency, a program supporting young musicians, disseminating knowledge, and developing the music scene.

Eight months of legal proceedings demanded significant resources: the team’s time, legal support, and organizational effort.

The Foundation’s work did not stop, but some projects had to be scaled back or postponed, as attention and funding were redirected toward defending the book. At some point, instead of developing and supporting the music scene, the team was forced to spend its energy defending what had already been created – and the practice of independent research came under pressure.

File № 91-23

File № 91-23

File № 91-23

How did a book about Kazakhstani music end up in court?

How did a book about Kazakhstani music end up in court?

How did a book about Kazakhstani music end up in court?

Imagine this:

Imagine this:

Imagine this:

you gather material, speak with musicians, dive into archives, trying to preserve an entire era in a single book. It is released, people read it, it becomes part of the cultural conversation. And then, suddenly – a ban. This is how the story of 91-23 begins – the first book about the history of Kazakhstani pop music to become the center of a legal dispute.

you gather material, speak with musicians, dive into archives, trying to preserve an entire era in a single book. It is released, people read it, it becomes part of the cultural conversation. And then, suddenly – a ban. This is how the story of 91-23 begins – the first book about the history of Kazakhstani pop music to become the center of a legal dispute.

What happened to the book?

What happened to the book?

Disclaimer: The case is currently pending review by the cassation court. The first-instance court’s decision has entered into force, but the interim measures – the withdrawal of the book from circulation – have been lifted.

Disclaimer: The case is currently pending review by the cassation court. The first-instance court’s decision has entered into force, but the interim measures – the withdrawal of the book from circulation – have been lifted.

November 30, 2024

The book 91-23. About Popular Music of Independent Kazakhstan was published.

March 2, 2025

filing of the lawsuit

The plaintiff demanded to:

• declare the book counterfeit;

• withdraw it from circulation and destroy all copies;

• recover compensation for copyright infringement – 167,880,000 tenge;

• recover compensation for moral damages – 27,000,000 tenge;

• recover all legal expenses.

March 11, 2025

Interim measures

The court temporarily prohibited the distribution of the book. The plaintiff’s claims to distress the Foundation’s accounts and seize property were denied.

November 30, 2024

The book 91-23. About Popular Music of Independent Kazakhstan was published.

March 2, 2025

filing of the lawsuit

The plaintiff demanded to:

• declare the book counterfeit;

• withdraw it from circulation and destroy all copies;

• recover compensation for copyright infringement – 167,880,000 tenge;

• recover compensation for moral damages – 27,000,000 tenge;

• recover all legal expenses.

March 11, 2025

Interim measures

The court temporarily prohibited the distribution of the book. The plaintiff’s claims to distress the Foundation’s accounts and seize property were denied.

April 21, 2025

Preliminary hearing

May 27, 2025

clarification of claims

The total claim was reduced to 111,920,000 tenge – the plaintiff recalculated the print run from 3,000 to 2,000 copies.

July 2, 2025

settlement discussions

The plaintiff proposed that the Foundation:

• issue a written apology;

• destroy the first print run;

• release a new edition with plaintiff-requested amendments;

• cover all legal expenses.

The Foundation proposed instead:

• not to destroy the existing print run, but to donate it to libraries and educational institutions. (This settlement option was rejected by the plaintiff.)

April 21, 2025

Preliminary hearing

May 27, 2025

clarification of claims

The total claim was reduced to 111,920,000 tenge – the plaintiff recalculated the print run from 3,000 to 2,000 copies.

July 2, 2025

settlement discussions

The plaintiff proposed that the Foundation:

• issue a written apology;

• destroy the first print run;

• release a new edition with plaintiff-requested amendments;

• cover all legal expenses.

The Foundation proposed instead:

• not to destroy the existing print run, but to donate it to libraries and educational institutions. (This settlement option was rejected by the plaintiff.)

November 30, 2024

The book 91-23. About Popular Music of Independent Kazakhstan was published

March 2, 2025

filing of the lawsuit

The plaintiff demanded to:

• declare the book counterfeit;

• withdraw it from circulation and destroy all copies;

• recover compensation for copyright infringement – 167,880,000 tenge;

• recover compensation for moral damages – 27,000,000 tenge;

• recover all legal expenses.

March 11, 2025

Interim measures

The court temporarily prohibited the distribution of the book.

The plaintiff’s claims to distress the Foundation’s accounts and seize property were denied.

April 21, 2025

preliminary hearing

May 27, 2025

clarification of claims

The total claim was reduced to 111,920,000 tenge – the plaintiff recalculated the print run from 3,000 to 2,000 copies.

The actual print run of the book had always been 2,000 copies.

July 2, 2025

settlement discussions

The plaintiff proposed that the Foundation:

• issue a written apology;

• destroy the first print run;

• release a new edition with plaintiff-requested amendments;

• cover all legal expenses.

The Foundation proposed instead:

• not to destroy the existing print run, but to donate it to libraries and educational institutions. (This settlement option was rejected by the plaintiff.)

Why the settlement was not signed

Why the settlement was not signed

It required the Foundation to admit a violation that had not been established in court, alter the content of the research, and destroy the existing print run. This contradicted the evidence and the very nature of the work.

Plaintiff’s motions during the trial

The plaintiff additionally claimed to:

• declare the documentary evidence falsified;

• subject the Foundation’s director (Nargiz Shukenova) to a polygraph test;

• appoint a psychological examination to assess his emotional suffering;

• hold the hearings in closed session.

The court denied all motions except the claim for closed hearings.

Why the polygraph and psychological examinations were rejected

Why the polygraph and psychological examinations were rejected

• A polygraph is not admissible as evidence in civil proceedings.

• Emotional distress does not determine whether a law was violated.

The subject of the dispute was whether copyright had been infringed — not personal feelings.

July 4, 2025

The plaintiff filed complaints against the judge and the trial process in several state bodies.

August 13, 2025

Решение суда первой инстанции.

first-instance court decision

First-instance court decision. The lawsuit was dismissed in full. The court recognized that the book:

• is not counterfeit;

• does not infringe copyright;

• is a research and educational work.

September 11-12, 2025

The plaintiff filed three appeals.

October 23, 2025

The plaintiff submitted a petition to withdraw the monetary claims.

October 28, 2025

The Batyr Foundation won the appeal

The appellate court upheld the lower court’s ruling:

the book is lawful and remains a research work with no copyright violations.

Appellate Court Ruling dated October 28

Appellate Court Ruling dated October 28

“Pursuant to Article 7 of the Law “On Copyright and Related Rights”, copyright protection applies to the form of expression of a work, not to the idea, theme, or fact referenced by it.”

“The publication was created and distributed as a literary-informational compendium, which does not require obtaining permissions for the simple mention of works for the purpose of analytical description.”

“A mere mention of a song title does not constitute reproduction or adaptation of a work and therefore does not infringe the author’s personal rights.”

“To recognize a copy as counterfeit, it is necessary to prove that the work has been used in an objective form. Since this was not proven, the reference to ‘automatic counterfeit status’ is unfounded and contradicts the law.”

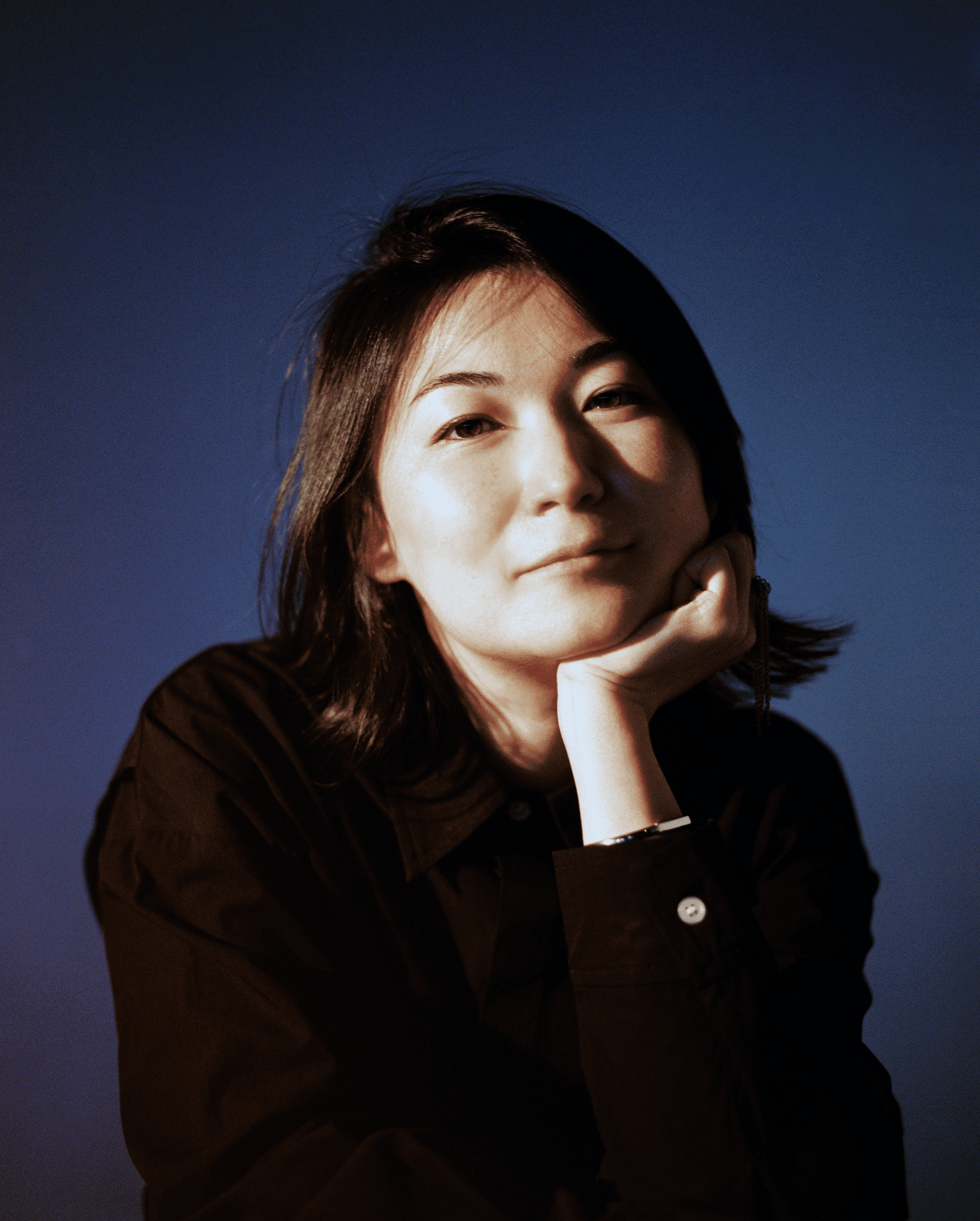

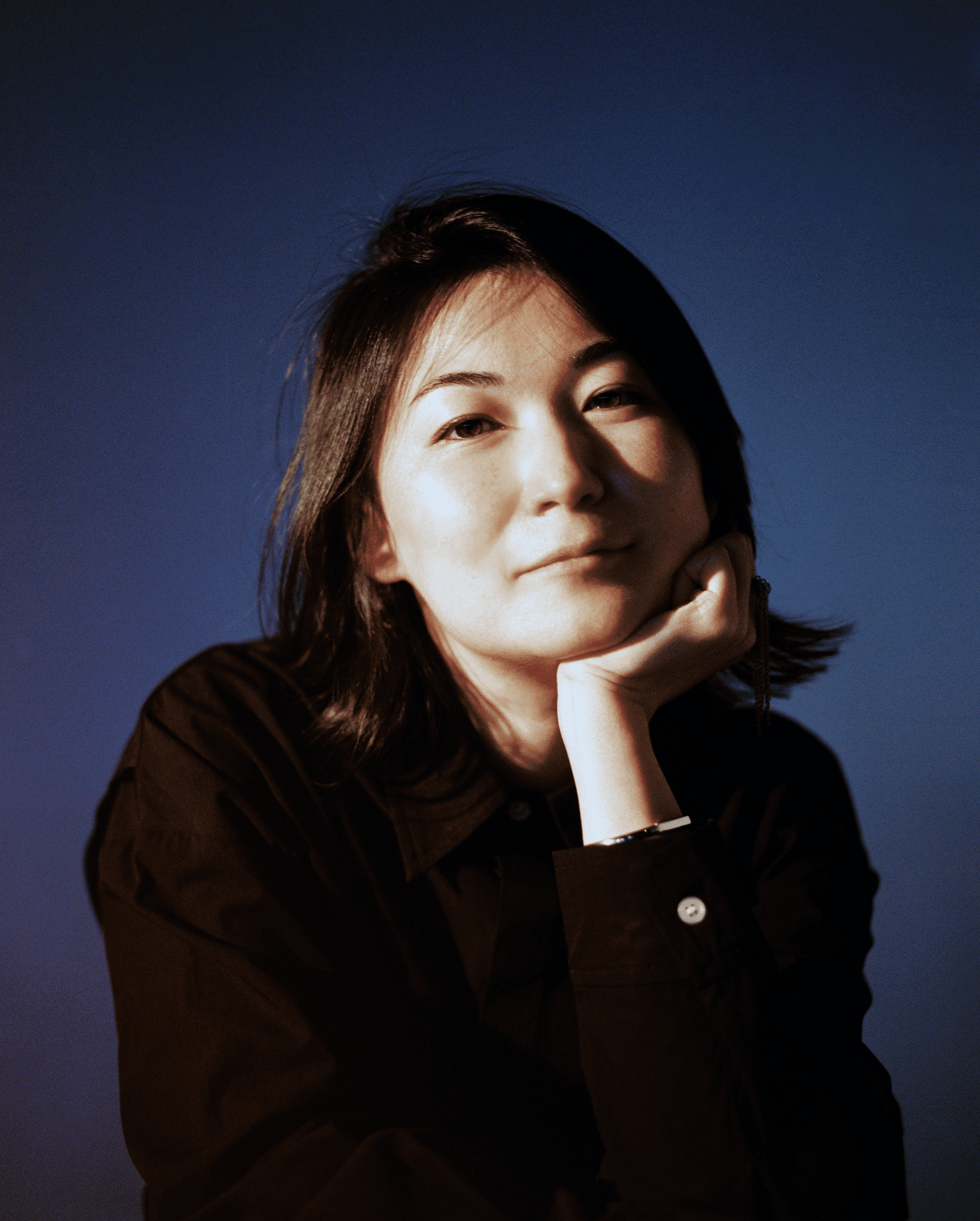

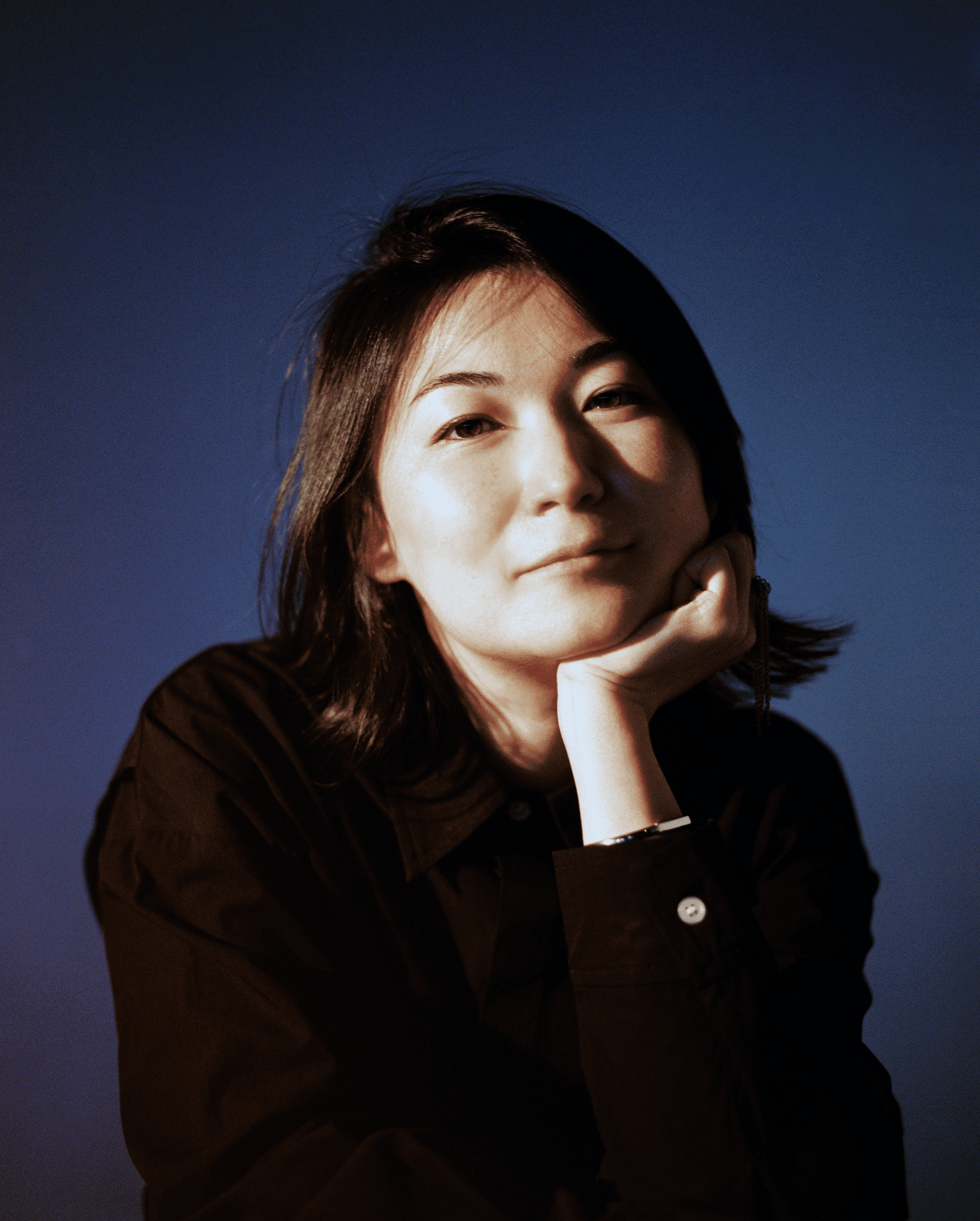

Statement by Nargiz Shukenova

Statement by Nargiz Shukenova

Director of the Batyr Foundation; producer of film, cultural, and art projects; founder of the independent film festival Clique Fest (2014–2018); co-founder of The Buhars

Director of the Batyr Foundation; producer of film, cultural, and art projects; founder of the independent film festival Clique Fest (2014–2018); co-founder of The Buhars

0:00/1:34

“I have been working with cultural heritage for seven years now, and I understand how much we have already lost. Even in the case of my uncle, Batyrkhan Shukenov – who had a team and understood the importance of building his own archive, yet still did not manage to complete everything – entire layers of his history and artistic practice have disappeared. The history of independent Kazakhstan spans more than thirty years, and during this time a vast amount of knowledge about ourselves has been lost. Yet it is precisely this knowledge that forms our shared language and sense of belonging. Without preserving this memory, we risk losing the foundation – the very thing that makes us a society.

What troubles me most is the so-called chilling effect that has spread throughout the community. I see how self-censorship has increased and how it has affected independent publishers, who have reduced programs related to local authors. This concerns everyone who wants to think, create meaning, and express an opinion. In Kazakhstan, cultural heritage is primarily handled by the state, but it is independent initiatives that give voice to different perspectives and create a fuller, living picture, enriching society. I don’t believe in a monopoly on memory – our book contains an entire collective of voices with different experiences and viewpoints. When you tell other people’s stories, disagreement is inevitable. It is impossible to control the narrative; in the diversity of opinions I see beauty and strength. It is important to preserve heritage ourselves, to create our own meanings, and to be prepared to resist. This is the price of freedom of expression. And – yes – you should always have a good lawyer and allies by your side.

The judge acknowledged that if the intellectual property itself is not reproduced, it cannot be considered a violation. Laws are made of words, and everyone interprets them differently. That is why it is so important to be attentive to a word, to remember the balance between the interests of the author and the interests of society, and to be ready to defend your rights.”

About the book

About the book

About the book

Thirty years of Kazakhstani pop music – from the first days of independence to the present – have been brought together in a single publication. 91–23 is the first major study of popular music in independent Kazakhstan, created from within: by authors who were part of the events, knew the artists personally, and witnessed the formation of the local scene.

It is an attempt to preserve not only facts, but also the atmosphere of the time.

Thirty years of Kazakhstani pop music – from the first days of independence to the present – have been brought together in a single publication. 91–23 is the first major study of popular music in independent Kazakhstan, created from within: by authors who were part of the events, knew the artists personally, and witnessed the formation of the local scene.

It is an attempt to preserve not only facts, but also the atmosphere of the time.

Months of work

Experts and contributors

Names of artists, bands, and producers

The historical period covered

Months of work

Experts and contributors

Names of artists, bands, and producers

The historical period covered

5 chapters

each chapter dedicated to a specific musical genre

Dozens of sources

from the archives of Novoye Pokolenie newspaper to YouTube comments and the Wayback Machine

2 languages

the Russian section

by former Esquire Kazakhstan editor-in-chief Alexandr Medvedev

the Kazakh section

by 98’Mag columnist Adil Aizharyk

5 chapters

each chapter dedicated to a specific musical genre

Dozens of sources

from the archives of Novoye Pokolenie newspaper to YouTube comments and the Wayback Machine

2 languages

the Russian section

by former Esquire Kazakhstan editor-in-chief Alexandr Medvedev

the Kazakh section

by 98’Mag columnist Adil Aizharyk

How the

КАК

Book Was Created

Book Was Created

For 91-23, executive editor and art director Malika Kokhan, together with Nargiz Shukenova, developed their own method for gathering and interpreting data. It emerged naturally from the context of Kazakhstan’s music scene – from the way music truly lives in the country: through people, venues, communities, and transitions between eras.

Instead of following preexisting models, the team studied local and international examples of popular science and nonfiction writing and built their own approach.

“We understood that we were working with fragmented facts that don’t always fit into a neat classification. To assemble a coherent picture of the country’s musical landscape, we invited people from within the scene – artists, producers, researchers. As co-authors we intentionally sought not only musicologists and scholars, but researchers and enthusiasts as we are,” Malika explains.

For 91-23, executive editor and art director Malika Kokhan, together with Nargiz Shukenova, developed their own method for gathering and interpreting data. It emerged naturally from the context of Kazakhstan’s music scene – from the way music truly lives in the country: through people, venues, communities, and transitions between eras.

Instead of following preexisting models, the team studied local and international examples of popular science and nonfiction writing and built their own approach.

“We understood that we were working with fragmented facts that don’t always fit into a neat classification. To assemble a coherent picture of the country’s musical landscape, we invited people from within the scene – artists, producers, researchers. As co-authors we intentionally sought not only musicologists and scholars, but researchers and enthusiasts as we are,” Malika explains.

The material was collected from living traces: memories, oral histories, archival clippings, YouTube comments, and the personal archives of experts. This allowed the team to compile an extensive list of artists, bands, producers, and collectives from 1991 to 2023. Thus, the book captures not only names, but snapshots of entire eras.

The timeline became not just a way to organize the material, but a tool for showing how the musical ecosystem changed: how some scenes emerged, others faded, and how sound followed the times.

“This is how we highlighted the connections between eras, shifts in the structure of the scene, and the influence of culture on society,” Malika adds.

The material was collected from living traces: memories, oral histories, archival clippings, YouTube comments, and the personal archives of experts. This allowed the team to compile an extensive list of artists, bands, producers, and collectives from 1991 to 2023. Thus, the book captures not only names, but snapshots of entire eras.

The timeline became not just a way to organize the material, but a tool for showing how the musical ecosystem changed: how some scenes emerged, others faded, and how sound followed the times.

“This is how we highlighted the connections between eras, shifts in the structure of the scene, and the influence of culture on society,” Malika adds.

91-23 is not a final answer but a study that leaves room for personal memory, dialogue, and multiple viewpoints. The book does not offer a single universal interpretation – instead, it invites conversation.

“Our goal was to create a dialogue between the book and its readers. 91–23 is a shared journey into the history of Kazakhstani music, not an encyclopedia or a monumental tome freezing collective knowledge in amber for centuries. We knew we couldn’t capture everything that has happened and is happening in the country’s musical and cultural landscape. But we deeply wanted to take the first step toward understanding our history – and ourselves – through the lens of Kazakhstani music,” Malika says.

91-23 is not a final answer but a study that leaves room for personal memory, dialogue, and multiple viewpoints. The book does not offer a single universal interpretation – instead, it invites conversation.

“Our goal was to create a dialogue between the book and its readers. 91–23 is a shared journey into the history of Kazakhstani music, not an encyclopedia or a monumental tome freezing collective knowledge in amber for centuries. We knew we couldn’t capture everything that has happened and is happening in the country’s musical and cultural landscape. But we deeply wanted to take the first step toward understanding our history – and ourselves – through the lens of Kazakhstani music,” Malika says.

91

23

Assylbek

Abdykulov

Assylbek

Abdykulov

The legal case surrounding 91-23 became more than a copyright dispute – it set a significant precedent for everyone involved in preserving cultural memory in Kazakhstan. It revealed how fragile the right to research can be when faced with an expansive interpretation of the law.

The legal case surrounding 91-23 became more than a copyright dispute – it set a significant precedent for everyone involved in preserving cultural memory in Kazakhstan. It revealed how fragile the right to research can be when faced with an expansive interpretation of the law.

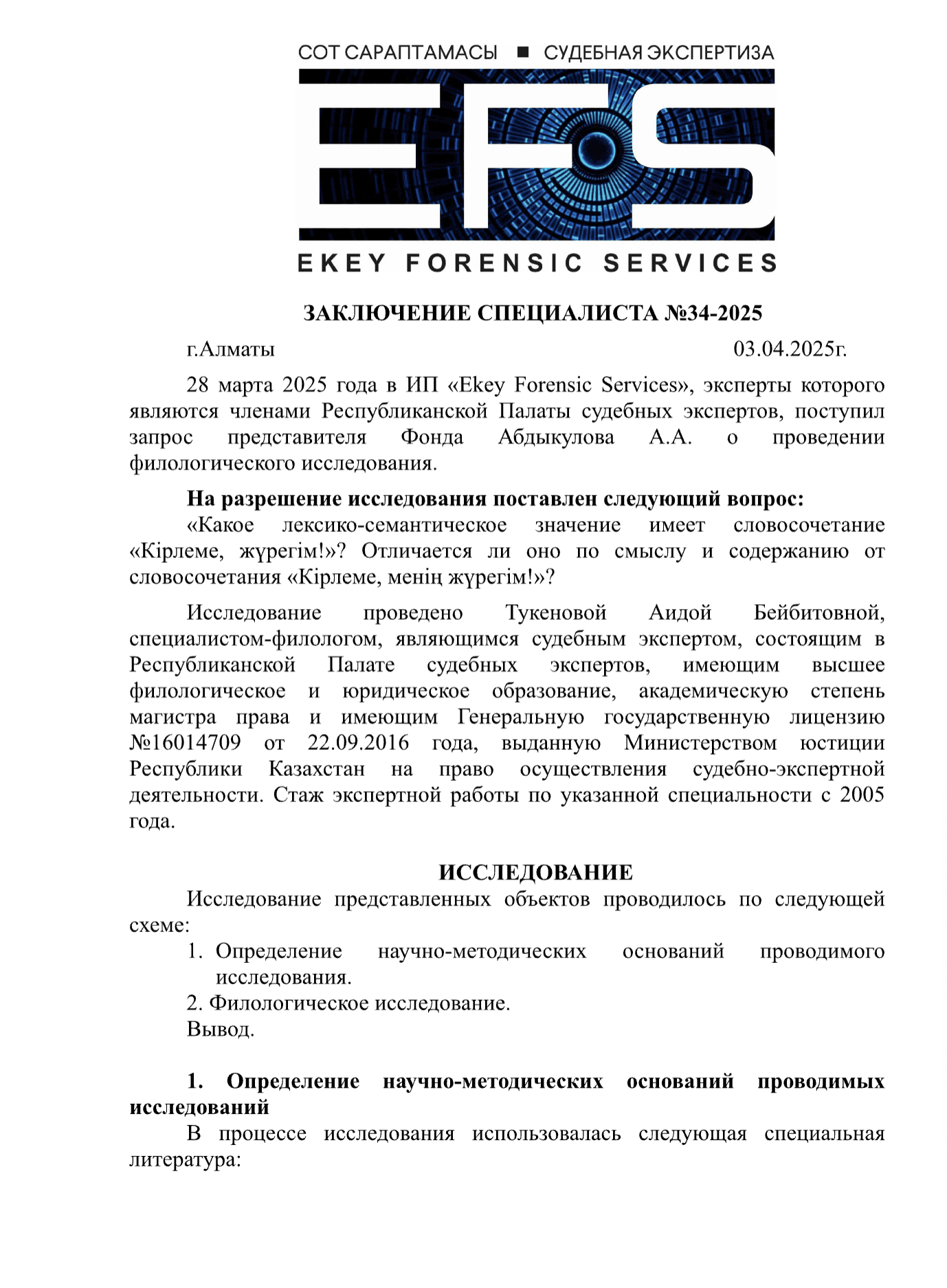

The commentary is provided by Assylbek Abdykulov

who represented the case in court – an expert in intellectual property law with more than 36 years of legal practice, including 20 years in the field of IP protection, and a registered patent attorney of the Republic of Kazakhstan.

The commentary is provided by Assylbek Abdykulov

who represented the case in court – an expert in intellectual property law with more than 36 years of legal practice, including 20 years in the field of IP protection, and a registered patent attorney of the Republic of Kazakhstan.

The legal case surrounding 91-23 became more than a copyright dispute – it set a significant precedent for everyone involved in preserving cultural memory in Kazakhstan. It revealed how fragile the right to research can be when faced with an expansive interpretation of the law.

The commentary is provided by Assylbek Abdykulov

who represented the case in court – an expert in intellectual property law with more than 36 years of legal practice, including 20 years in the field of IP protection, and a registered patent attorney of the Republic of Kazakhstan.

“Our key task was to demonstrate that the law distinguishes between the protection of a work’s form of expression and the right to describe historical facts,” Assylbek Abdykulov explains. “We did not dispute the plaintiff’s authorship, but we insisted that the nature of the research itself falls under the principle of free use.”

The defense strategy was built on a consistent explanation to the court of the fundamental difference between “mentioning” a work in a cultural context and “reproducing” it. Mr. Abdykulov emphasized that 91-23 contains no musical notation, no lyrics, and no other objective forms of the plaintiff’s works. Referring to Article 15 of the Law of the Republic of Kazakhstan “On Copyright and Related Rights,” the legal team maintained that copyright protection does not extend to titles, ideas, or facts, but only to their unique form of expression.

“We conducted a detailed analysis of every contested episode in the book,” the lawyer notes. “Our position was that mentioning song titles in a historical overview is not a violation, but citation for academic and informational purposes – explicitly permitted by law. The court agreed with this approach, affirming that research activity should not be paralyzed by the need to obtain permission for every mention.”

The victory in this case was achieved thanks to an in-depth development of the legal position and the ability to convey the essence of the research method to the court. This case shows that a well-constructed legal strategy can protect not only a specific project, but also strengthen legal guarantees for the entire field of cultural research in Kazakhstan.

Legal Outcome: The court’s decision on 91-23 established an important precedent clearly distinguishing between copyright infringement and lawful academic research. It confirmed that cultural studies and history have the right to exist without the risk of being accused of “counterfeiting” for the simple mention of cultural artifacts.

“Our key task was to demonstrate that the law distinguishes between the protection of a work’s form of expression and the right to describe historical facts,” Assylbek Abdykulov explains. “We did not dispute the plaintiff’s authorship, but we insisted that the nature of the research itself falls under the principle of free use.”

The defense strategy was built on a consistent explanation to the court of the fundamental difference between “mentioning” a work in a cultural context and “reproducing” it. Mr. Abdykulov emphasized that 91-23 contains no musical notation, no lyrics, and no other objective forms of the plaintiff’s works. Referring to Article 15 of the Law of the Republic of Kazakhstan “On Copyright and Related Rights,” the legal team maintained that copyright protection does not extend to titles, ideas, or facts, but only to their unique form of expression.

“We conducted a detailed analysis of every contested episode in the book,” the lawyer notes. “Our position was that mentioning song titles in a historical overview is not a violation, but citation for academic and informational purposes – explicitly permitted by law. The court agreed with this approach, affirming that research activity should not be paralyzed by the need to obtain permission for every mention.”

The victory in this case was achieved thanks to an in-depth development of the legal position and the ability to convey the essence of the research method to the court. This case shows that a well-constructed legal strategy can protect not only a specific project, but also strengthen legal guarantees for the entire field of cultural research in Kazakhstan.

Legal Outcome: The court’s decision on 91-23 established an important precedent clearly distinguishing between copyright infringement and lawful academic research. It confirmed that cultural studies and history have the right to exist without the risk of being accused of “counterfeiting” for the simple mention of cultural artifacts.

The Legal Context of the Dispute

The Legal Context of the Dispute

What is a lawsuit?

A lawsuit is an official document that initiates a court proceeding. In it, the plaintiff outlines the essence of the conflict, indicates the alleged violation of his rights, and states his claims toward the defendant (e.g., to prohibit distribution of the book or recognize authorship).

What is a response to a lawsuit?

A response to a lawsuit is the defendant’s written position submitted to the court. It contains arguments and evidence that refute or challenge the plaintiff’s claims.

How the Copyright is Regulated in Kazakhstan?

Kazakhstan’s copyright system is based on three key documents: • The Constitution of the Republic of Kazakhstan – guarantees the protection of property, freedom of speech, and freedom of creative expression. • The Civil Code – defines intellectual property as the exclusive right to the results of creative activity (works of science, literature, art, etc.). • The Law of the Republic of Kazakhstan “On Copyright and Related Rights” - specifically regulates authors’ personal (non-property) and property rights, as well as the mechanisms for their protection.

Which International Agreements Apply?

Kazakhstan is a party to several major international conventions, including: • The Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works • The Universal Copyright Convention • The Convention for the Protection of Producers of Phonograms • The International Convention for the Protection of Performers and Broadcasting Organizations • Treaties of the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO)

What Is the Principle of “Free Use”?

This legal principle allows the use of fragments of works for research, educational, and cultural purposes without the right holder’s permission, provided that the author and source are cited. A violation occurs when a work is fully copied, used commercially, or distorted without the author’s consent.

Why Was It Impossible to List Authorship in Every Episode of 91-23?

91-23 is a research project. The book contains no lyrics, no sheet music, no scores – only facts, dates, and names. The court explicitly stated: a simple mention of a song title in an analytical description is not considered “use” under the law and does not require permission. The authors do not monetize other people’s copyrighted works; they document history and cultural context. In places where authorship is essential for understanding the material, it is clearly stated and preserved. The book was already extensive. According to our calculations, listing full authorship for every individual mention would have added over 200 pages, making the publication bulky and less accessible.

What Steps Are Taken When a Conflict Arises?

• Pre-trial actions – claims, negotiations, attempts to settle the conflict. • Judicial protection – recognition of rights, cessation of violations, compensation for damages, and restoration of reputation. • During the court process, each party must prove its arguments by submitting documents, evidence, expert analyses, and specialist opinions.

What is a lawsuit?

A lawsuit is an official document that initiates a court proceeding. In it, the plaintiff outlines the essence of the conflict, indicates the alleged violation of his rights, and states his claims toward the defendant (e.g., to prohibit distribution of the book or recognize authorship).

What is a response to a lawsuit?

A response to a lawsuit is the defendant’s written position submitted to the court. It contains arguments and evidence that refute or challenge the plaintiff’s claims.

How the Copyright is Regulated in Kazakhstan?

Kazakhstan’s copyright system is based on three key documents: • The Constitution of the Republic of Kazakhstan – guarantees the protection of property, freedom of speech, and freedom of creative expression. • The Civil Code – defines intellectual property as the exclusive right to the results of creative activity (works of science, literature, art, etc.). • The Law of the Republic of Kazakhstan “On Copyright and Related Rights” - specifically regulates authors’ personal (non-property) and property rights, as well as the mechanisms for their protection.

Which International Agreements Apply?

Kazakhstan is a party to several major international conventions, including: • The Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works • The Universal Copyright Convention • The Convention for the Protection of Producers of Phonograms • The International Convention for the Protection of Performers and Broadcasting Organizations • Treaties of the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO)

What Is the Principle of “Free Use”?

This legal principle allows the use of fragments of works for research, educational, and cultural purposes without the right holder’s permission, provided that the author and source are cited. A violation occurs when a work is fully copied, used commercially, or distorted without the author’s consent.

Why Was It Impossible to List Authorship in Every Episode of 91-23?

91-23 is a research project. The book contains no lyrics, no sheet music, no scores – only facts, dates, and names. The court explicitly stated: a simple mention of a song title in an analytical description is not considered “use” under the law and does not require permission. The authors do not monetize other people’s copyrighted works; they document history and cultural context. In places where authorship is essential for understanding the material, it is clearly stated and preserved. The book was already extensive. According to our calculations, listing full authorship for every individual mention would have added over 200 pages, making the publication bulky and less accessible.

What Steps Are Taken When a Conflict Arises?

• Pre-trial actions – claims, negotiations, attempts to settle the conflict. • Judicial protection – recognition of rights, cessation of violations, compensation for damages, and restoration of reputation. • During the court process, each party must prove its arguments by submitting documents, evidence, expert analyses, and specialist opinions.

What is a lawsuit?

A lawsuit is an official document that initiates a court proceeding. In it, the plaintiff outlines the essence of the conflict, indicates the alleged violation of his rights, and states his claims toward the defendant (e.g., to prohibit distribution of the book or recognize authorship).

What is a response to a lawsuit?

A response to a lawsuit is the defendant’s written position submitted to the court. It contains arguments and evidence that refute or challenge the plaintiff’s claims.

How the Copyright is Regulated in Kazakhstan?

Kazakhstan’s copyright system is based on three key documents: • The Constitution of the Republic of Kazakhstan – guarantees the protection of property, freedom of speech, and freedom of creative expression. • The Civil Code – defines intellectual property as the exclusive right to the results of creative activity (works of science, literature, art, etc.). • The Law of the Republic of Kazakhstan “On Copyright and Related Rights” - specifically regulates authors’ personal (non-property) and property rights, as well as the mechanisms for their protection.

Which International Agreements Apply?

Kazakhstan is a party to several major international conventions, including: • The Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works • The Universal Copyright Convention • The Convention for the Protection of Producers of Phonograms • The International Convention for the Protection of Performers and Broadcasting Organizations • Treaties of the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO)

What Is the Principle of “Free Use”?

This legal principle allows the use of fragments of works for research, educational, and cultural purposes without the right holder’s permission, provided that the author and source are cited. A violation occurs when a work is fully copied, used commercially, or distorted without the author’s consent.

Why Was It Impossible to List Authorship in Every Episode of 91-23?

91-23 is a research project. The book contains no lyrics, no sheet music, no scores – only facts, dates, and names. The court explicitly stated: a simple mention of a song title in an analytical description is not considered “use” under the law and does not require permission. The authors do not monetize other people’s copyrighted works; they document history and cultural context. In places where authorship is essential for understanding the material, it is clearly stated and preserved. The book was already extensive. According to our calculations, listing full authorship for every individual mention would have added over 200 pages, making the publication bulky and less accessible.

What Steps Are Taken When a Conflict Arises?

• Pre-trial actions – claims, negotiations, attempts to settle the conflict. • Judicial protection – recognition of rights, cessation of violations, compensation for damages, and restoration of reputation. • During the court process, each party must prove its arguments by submitting documents, evidence, expert analyses, and specialist opinions.

The first authorial photobook exploring the aesthetics of contemporary interior design in Kazakhstan. The book features more than 30 projects by local designers, presented through the photographer’s subjective lens.

Damir Otegen

Seeing Space

Kazakhstan

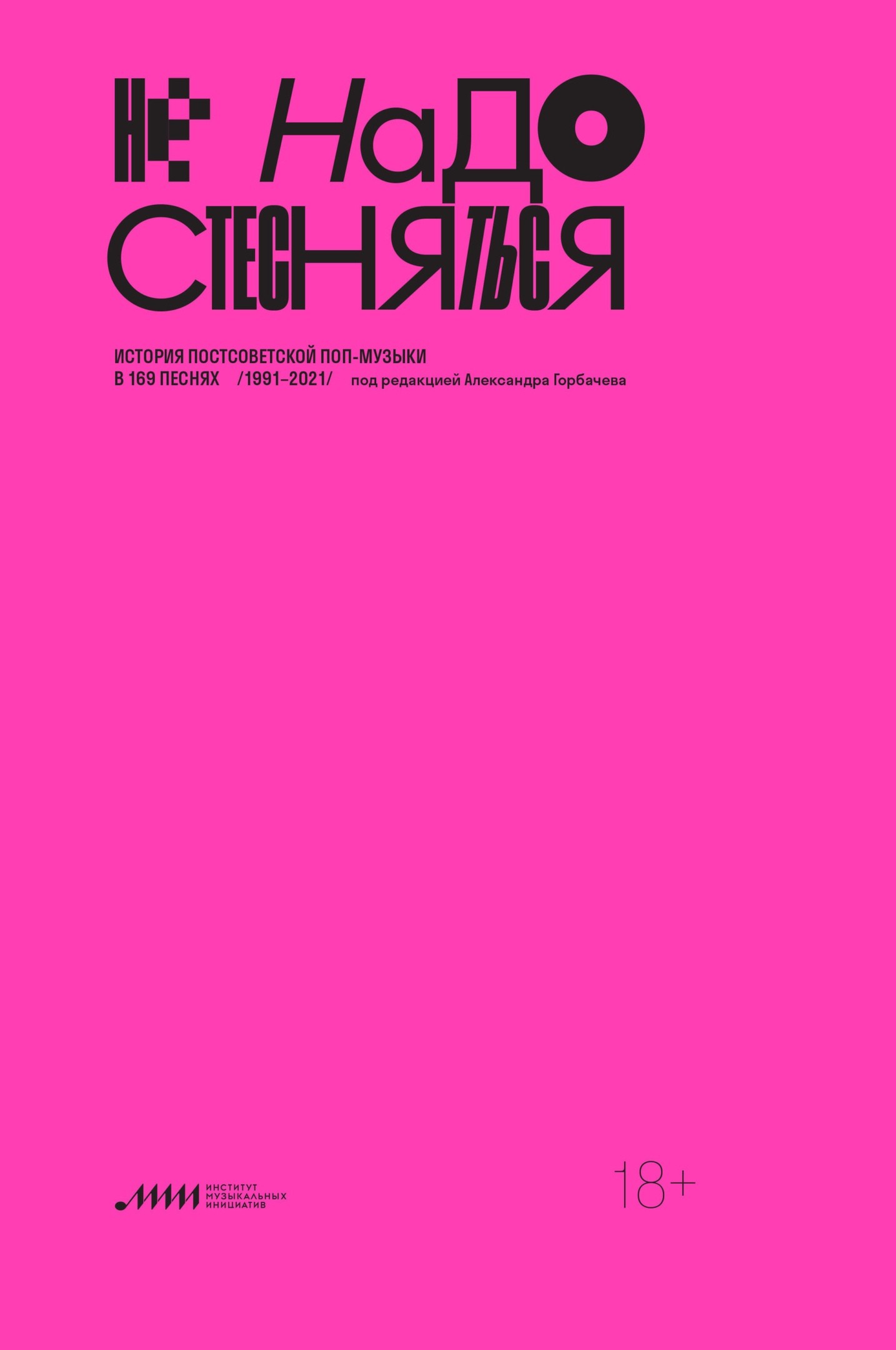

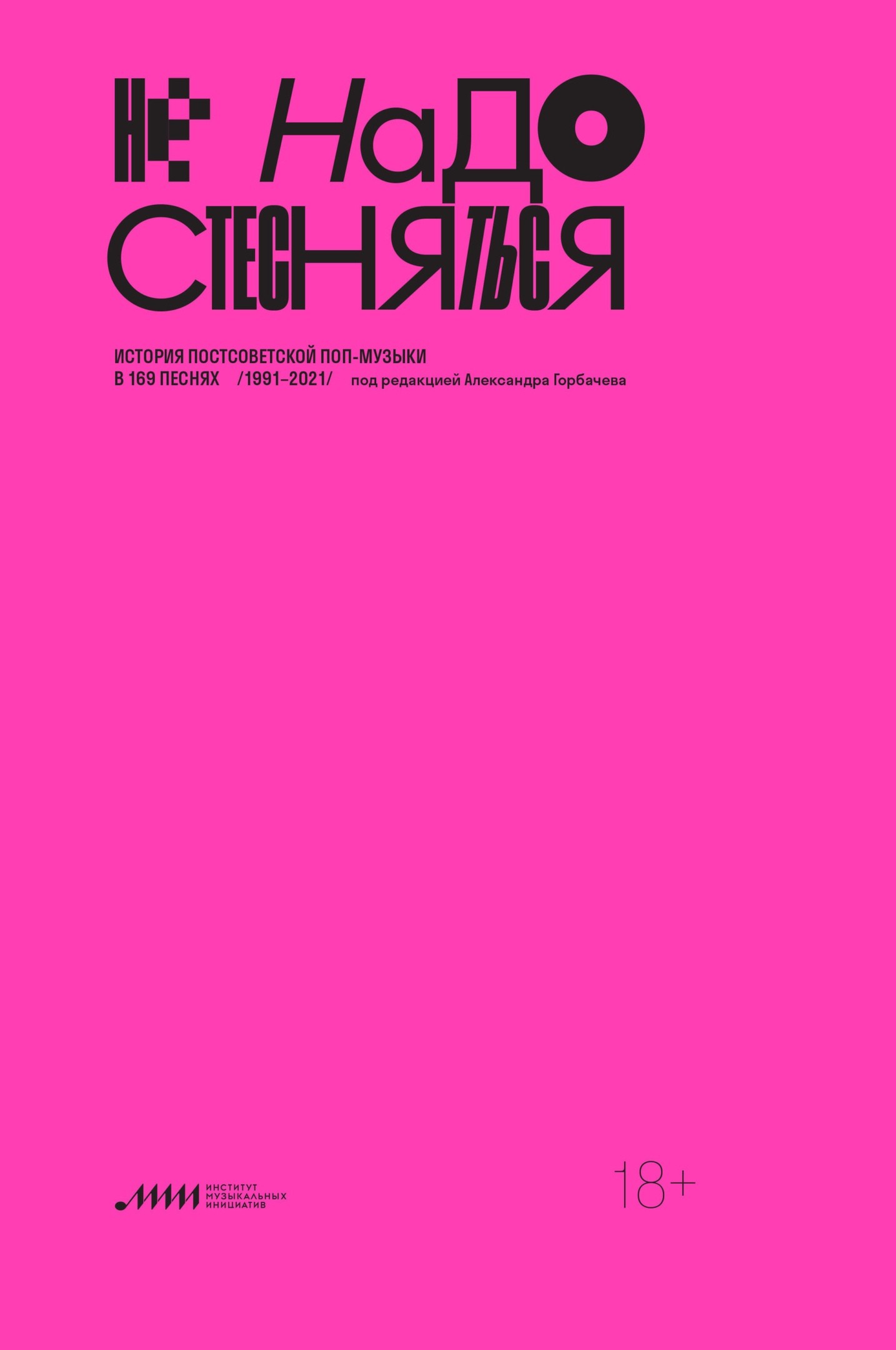

A history of post-Soviet pop music told through 169 songs. Each chapter centers on a specific hit, enriched with memories and cultural context. Created by an independent researcher, the book has become a unique chronicle of regional cultural memory.

Alexandr Gorbachev

Don't Be Shy

Russia

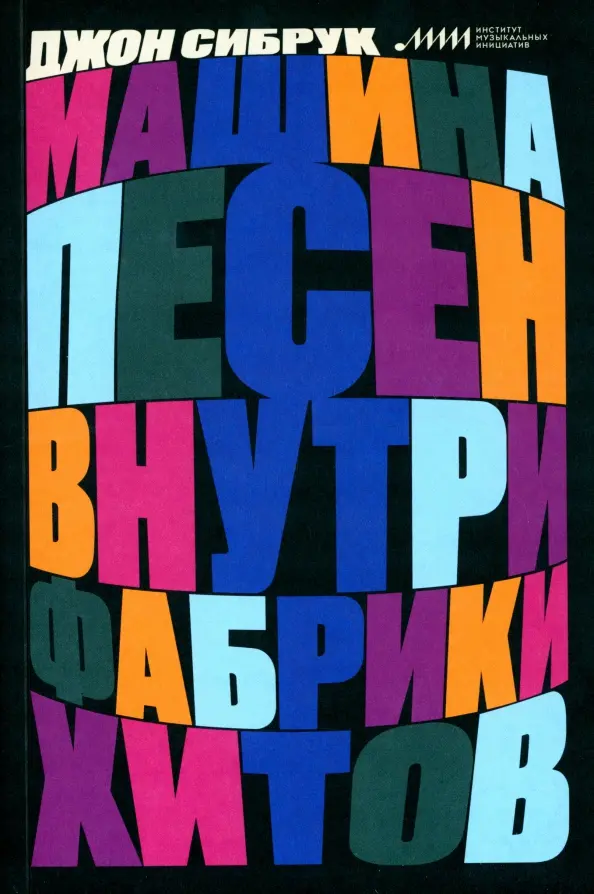

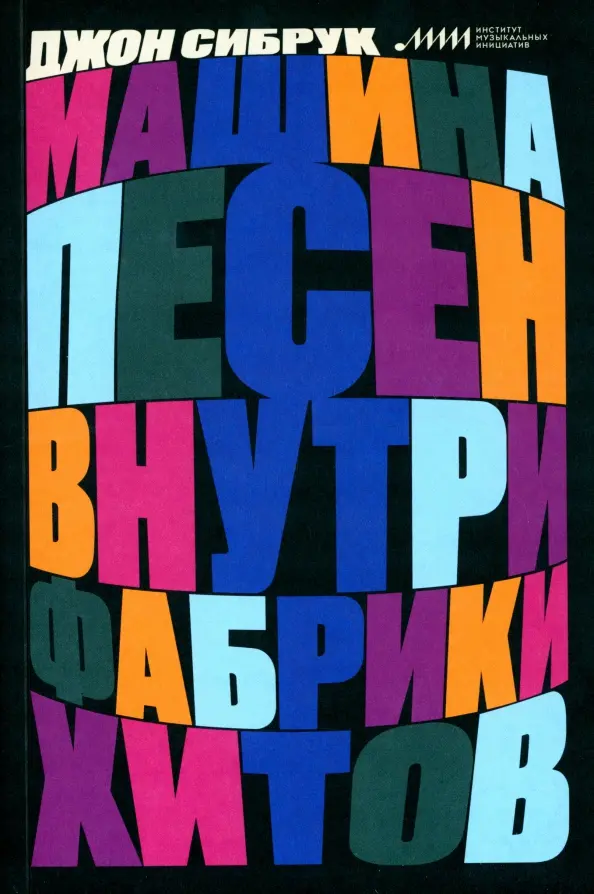

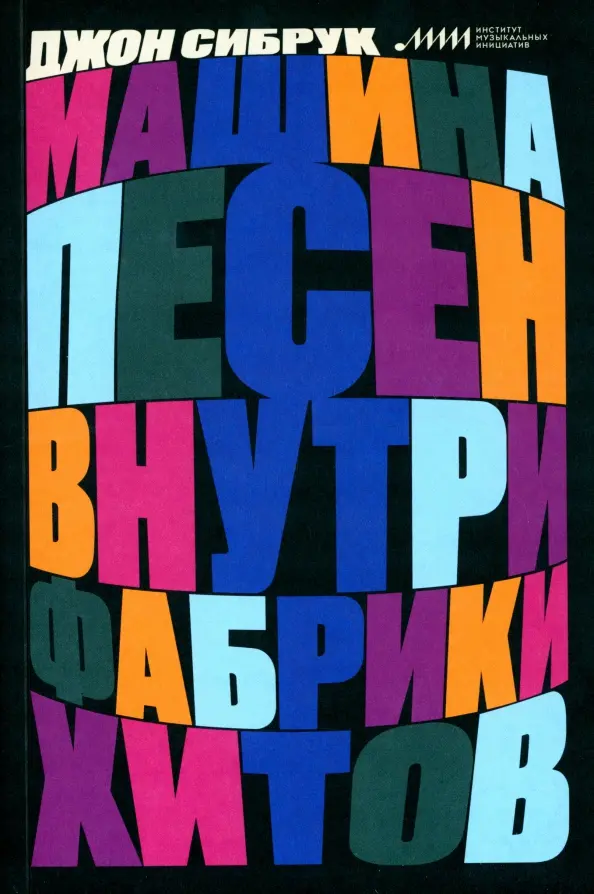

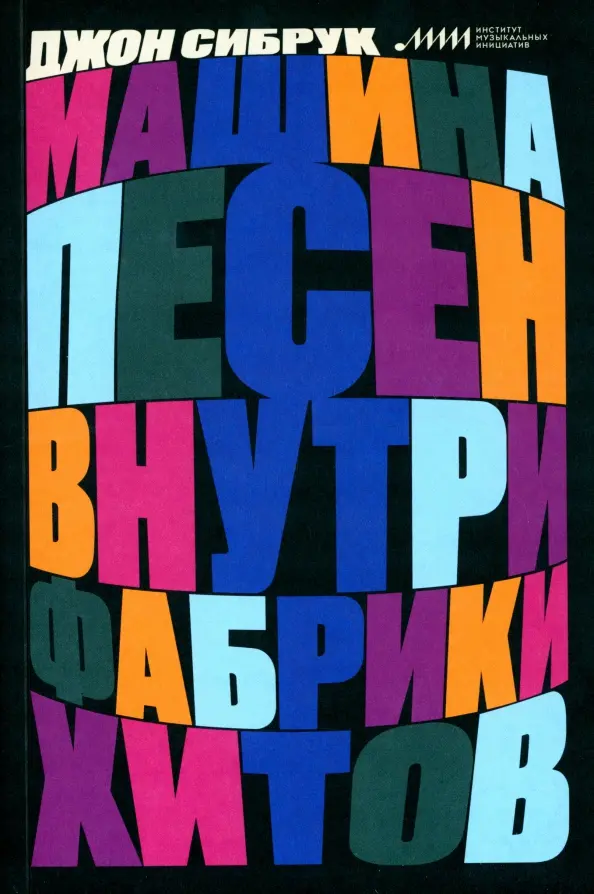

A journalistic investigation into how global pop-music production centers operate – from the Korean industry to Swedish songwriters. One of the first deep looks into what lies behind the world’s pop scene.

John Seabrook

The Song Machine: Inside the Hit Factory

USA

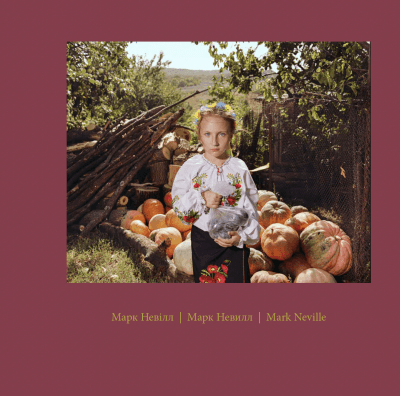

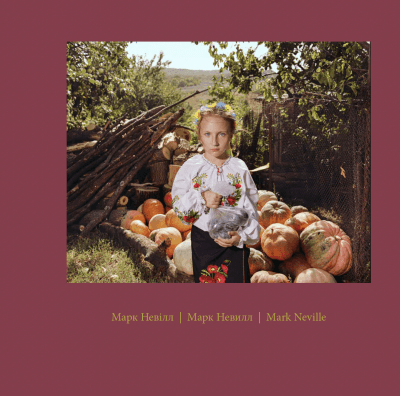

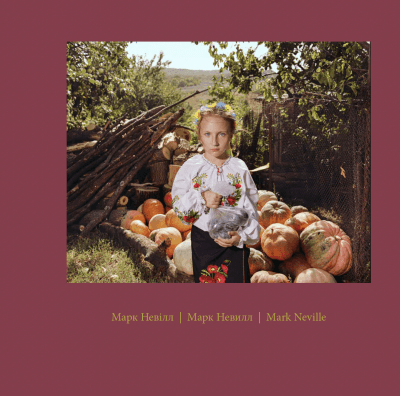

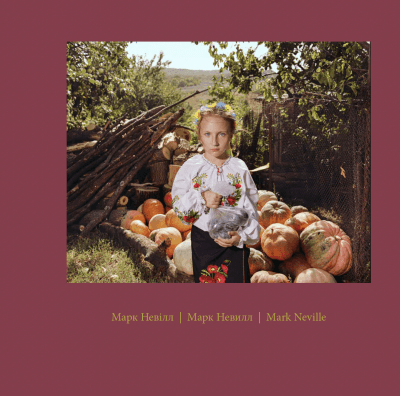

A photobook combining portraits of Ukrainians with personal stories and research. Published as an independent artistic activist project; distributed for free in Europe and the United States to draw attention to the war.

Mark Neville

Stop Tanks With Books

United Kingdom / Ukraine

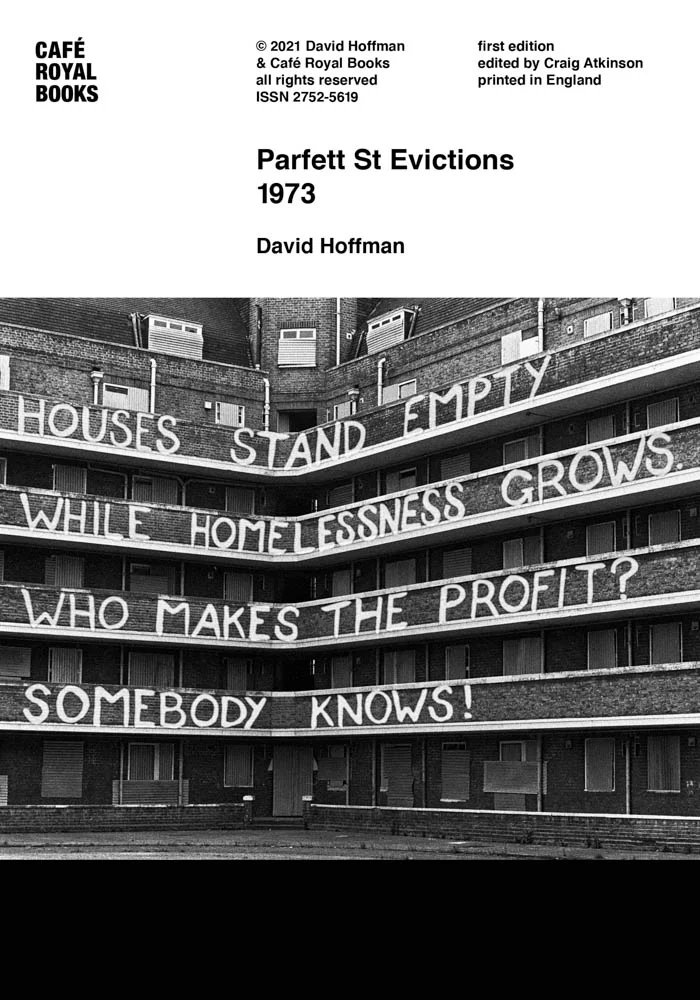

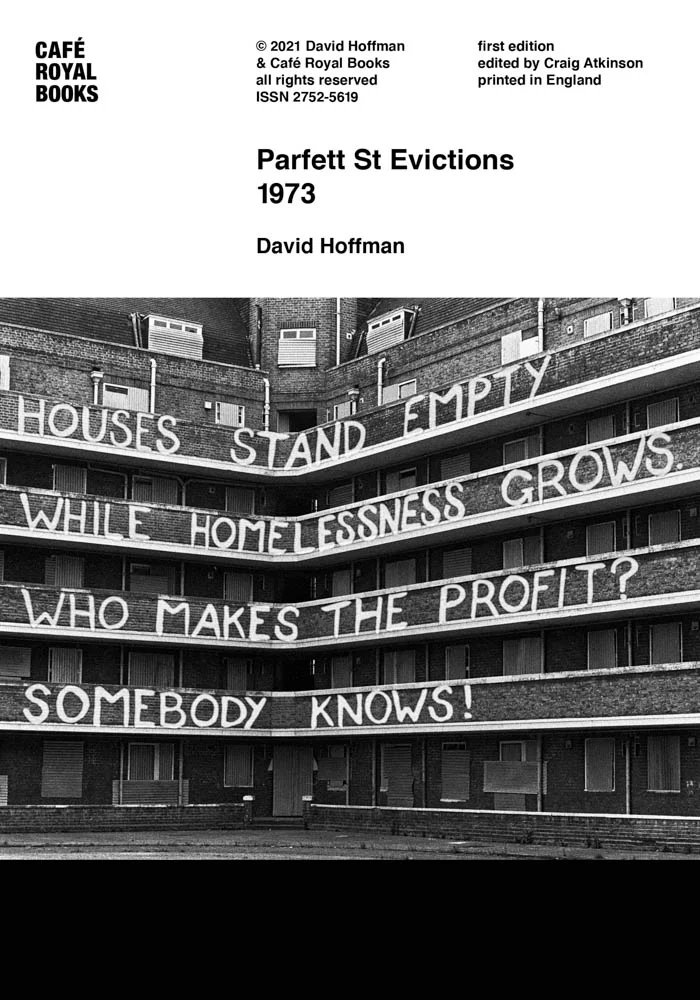

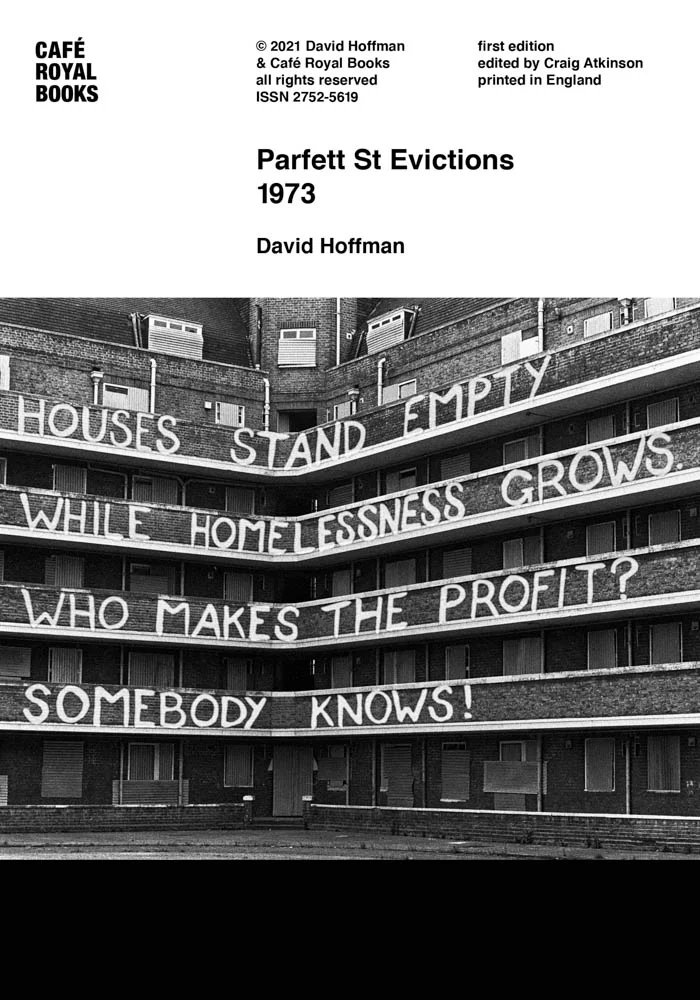

An independent publisher producing small-edition photobooks and zines. Since 2005, it has published documentary series about British everyday life, making them accessible to a wide audience.

Café Royal Books

United Kingdom

A cult photobook first published in 1968 by independent artists. The authors wanted images that “provoke thought.” Though the project existed for less than a year, it transformed the visual language of Japanese photography and became a point of departure for an entire generation of artists.

Provoke

Japan (Reprint Edition, Tokyo)

A DIY photozine about the city of Preston that grew into a full-scale project with exhibitions, lectures, and publications. An example of how a local story can become a cultural phenomenon without government involvement.

Preston is My Paris

United Kingdom

Global Examples of Independent Cultural Projects

Global Examples of Independent Cultural Projects

91-23 is the first book about the pop music of independent Kazakhstan. Similar initiatives exist worldwide: they are created by researchers, artists, and independent publishers to preserve cultural memory and document what might otherwise be forgotten.

91-23 is the first book about the pop music of independent Kazakhstan. Similar initiatives exist worldwide: they are created by researchers, artists, and independent publishers to preserve cultural memory and document what might otherwise be forgotten.

91-23 is the first book about the pop music of independent Kazakhstan. Similar initiatives exist worldwide: they are created by researchers, artists, and independent publishers to preserve cultural memory and document what might otherwise be forgotten.

Damir Otegen

The first authorial photobook exploring the aesthetics of contemporary interior design in Kazakhstan. The book features more than 30 projects by local designers, presented through the photographer’s subjective lens.

Damir Otegen

Seeing Space

Kazakhstan

Alexandr Gorbachev

John Seabrook

Mark Neville

Cafe Royal Books

Preston is My Paris

Provoke

Damir Otegen

The first authorial photobook exploring the aesthetics of contemporary interior design in Kazakhstan. The book features more than 30 projects by local designers, presented through the photographer’s subjective lens.

Damir Otegen

Seeing Space

Kazakhstan

Alexandr Gorbachev

John Seabrook

Mark Neville

Cafe Royal Books

Preston is My Paris

Provoke

What Researchers Say

What the Keepers of Heritage Say?

We spoke with researchers, historians, cultural theorists, and members of the music industry to hear their perspectives on 91-23 and the events surrounding it. Their comments highlight the book’s value, the importance of documenting cultural history, and the broader questions raised by the conflict.

We spoke with researchers, historians, cultural theorists, and members of the music industry to hear their perspectives on 91-23 and the events surrounding it. Their comments highlight the book’s value, the importance of documenting cultural history, and the broader questions raised by the conflict.

We spoke with researchers, historians, cultural theorists, and members of the music industry to hear their perspectives on 91-23 and the events surrounding it. Their comments highlight the book’s value, the importance of documenting cultural history, and the broader questions raised by the conflict.

Nariman Shelekpayev

Professor, Central Asian History and Culture, Yale University

Why is cultural research still poorly supported in Kazakhstan?

“In Kazakhstan it practically doesn’t exist. There are one or two exceptional cases, but overall there is no consistent support for independent research at the university level, or it is extremely limited. Everything depends on private foundations or individual patrons – these are exceptions, not the norm. It is important not to confuse culture with ideology, with religion, or with promoting particular individuals. Culture does not belong to the state, and without it there can be no progress.”

Why is 91-23 important for Kazakhstan?

“I find this book valuable because it serves as a compendium of information accompanied by professionally written essays. It fills a gap that no one had addressed before. If the authors hadn’t done this work, the material simply wouldn’t exist. The book is useful as a teaching resource for researchers and educators, for music lovers, and as a reference guide. To this day, there is no more comprehensive text on the history of Kazakhstani pop music than this book.”

Why don’t local voices reach a wider audience?

“Talented voices always find their audience – it’s a matter of time. What matters is not the quantity of listeners, but the quality of the audience. Whether they are local or global doesn’t matter if the work lacks meaning and substance. Everything that is meant to bloom will bloom.”

Нариман Шелекпаев

Nariman Shelekpayev

Профессор истории и культуры Центральной Азии, Йельский Университет

Professor, Central Asian History and Culture, Yale University

Nariman Shelekpayev

Professor, Central Asian History and Culture, Yale University

Why is cultural research still poorly supported in Kazakhstan?

“In Kazakhstan it practically doesn’t exist. There are one or two exceptional cases, but overall there is no consistent support for independent research at the university level, or it is extremely limited. Everything depends on private foundations or individual patrons – these are exceptions, not the norm. It is important not to confuse culture with ideology, with religion, or with promoting particular individuals. Culture does not belong to the state, and without it there can be no progress.”

Why is 91-23 important for Kazakhstan?

“I find this book valuable because it serves as a compendium of information accompanied by professionally written essays. It fills a gap that no one had addressed before. If the authors hadn’t done this work, the material simply wouldn’t exist. The book is useful as a teaching resource for researchers and educators, for music lovers, and as a reference guide. To this day, there is no more comprehensive text on the history of Kazakhstani pop music than this book.”

Why don’t local voices reach a wider audience?

“Talented voices always find their audience – it’s a matter of time. What matters is not the quantity of listeners, but the quality of the audience. Whether they are local or global doesn’t matter if the work lacks meaning and substance. Everything that is meant to bloom will bloom.”

Nariman Shelekpayev

Professor, Central Asian History and Culture, Yale University

Raushan Jumaniyazova

PhD in Art Studies, Kazakh National Conservatory named after Kurmangazy

Zira Nauryzbay

PhD in Philosophy, Cultural Theorist, author of academic and journalistic works

Why didn’t we write about everyone, and why are some covered in more detail than others?

“The ethical principles of academic writing require attribution only where it affects conclusions or when the specific work under analysis is itself the subject of discussion. These standards are fully observed in the book. This approach also aligns with the principles outlined in the Chicago Manual of Style (chs. 14-15), which allow selective attribution in cultural studies texts when justified by the structure of the work.”

What prevents people from speaking about Kazakhstani culture professionally and freely?

“If we think about a professional dialogue on Kazakhstani culture, we face a historically formed cultural ‘customs checkpoint’ – a system full of turnstiles and prohibitions. One of the first obstacles is the post-Soviet colonial inertia of terminology. We are still describing our culture in the language of someone else’s canon. Expertise is often replaced by a stamp of approval, and honest debate by the ‘correct’ phrasing. As a result, criticism becomes softened, discussions become sluggish or disappear entirely. Without criticism, development is hard to imagine.”

Raushan Jumaniyazova

PhD in Art Studies, Kazakh National Conservatory named after Kurmangazy

Zira Nauryzbay

PhD in Philosophy, Cultural Theorist, author of academic and journalistic works

Why didn’t we write about everyone, and why are some covered in more detail than others?

“The ethical principles of academic writing require attribution only where it affects conclusions or when the specific work under analysis is itself the subject of discussion. These standards are fully observed in the book. This approach also aligns with the principles outlined in the Chicago Manual of Style (chs. 14-15), which allow selective attribution in cultural studies texts when justified by the structure of the work.”

What prevents people from speaking about Kazakhstani culture professionally and freely?

“If we think about a professional dialogue on Kazakhstani culture, we face a historically formed cultural ‘customs checkpoint’ – a system full of turnstiles and prohibitions. One of the first obstacles is the post-Soviet colonial inertia of terminology. We are still describing our culture in the language of someone else’s canon. Expertise is often replaced by a stamp of approval, and honest debate by the ‘correct’ phrasing. As a result, criticism becomes softened, discussions become sluggish or disappear entirely. Without criticism, development is hard to imagine.”

What the Keepers of Heritage Say?

What the Keepers of Heritage Say?

What the Keepers of Heritage Say?

Musical memory lives not only in archives but also in the hands of sellers, professors, listeners, and street musicians. Everyone who keeps the sound alive keeps the culture alive. Each answer appears as a short quote + expanded audio versions are available for some interviews.

Musical memory lives not only in archives but also in the hands of sellers, professors, listeners, and street musicians. Everyone who keeps the sound alive keeps the culture alive. Each answer appears as a short quote + expanded audio versions are available for some interviews.

The history of music is not only dates and facts – it is the living voices of those who remember it, study it, and carry it forward. The book gathers perspectives from heirs to musical traditions, cultural experts, festival organizers, musicians, vintage record sellers – all those who, in their own way, preserve and transmit heritage.

They speak about why books like 91-23 matter, how the perception of music has changed over the decades, what it means to work with memory, and why openness to the new is essential.

The history of music is not only dates and facts – it is the living voices of those who remember it, study it, and carry it forward. The book gathers perspectives from heirs to musical traditions, cultural experts, festival organizers, musicians, vintage record sellers – all those who, in their own way, preserve and transmit heritage.

They speak about why books like 91-23 matter, how the perception of music has changed over the decades, what it means to work with memory, and why openness to the new is essential.

The history of music is not only dates and facts – it is the living voices of those who remember it, study it, and carry it forward. The book gathers perspectives from heirs to musical traditions, cultural experts, festival organizers, musicians, vintage record sellers – all those who, in their own way, preserve and transmit heritage.

They speak about why books like 91-23 matter, how the perception of music has changed over the decades, what it means to work with memory, and why openness to the new is essential.

Liora Eisenberg

Harvard MA, PhD candidate at Harvard, Princeton graduate (summa cum laude, Phi Beta Kappa), recipient of the Blavatnik Archive Research Fellowship, American Councils Title VIII Eurasia Research Scholar Grant, and Critical Language Scholarship.

How is heritage preserved today? Is it possible to write about the deceased? About the living? And how should it be done?

“Kazakhstani musical heritage is preserved… somewhat. Traditional genres – ethnic and folk music – are maintained better: festivals are held, there is the Dombra Day. But Soviet pop of the 1950s-60s is almost unstudied. Names like Yeskendir Khasangaliyev or early ensembles such as Aigul and Zhetygen are barely written about. Meanwhile, Dos-Mukasan survived in public memory, partly thanks to the film, and became part of the retro canon.

Writing about the deceased is of course possible, though it is challenging – there are still relatives and loved ones you don’t want to hurt. Writing about the living is even harder – there is always a risk of breaking unspoken rules about what can or cannot be mentioned.

For me, the key is context: cultural, historical, political. I don’t like when groups call themselves ‘the first’ in a genre or in using certain instruments. In Kazakhstan, I’ve heard at least three different bands make such claims. Without understanding roots and circumstances, such statements distort the picture – and we lose an accurate view of history.”

Liora Eisenberg

Harvard MA, PhD candidate at Harvard, Princeton graduate (summa cum laude, Phi Beta Kappa), recipient of the Blavatnik Archive Research Fellowship, American Councils Title VIII Eurasia Research Scholar Grant, and Critical Language Scholarship.

How is heritage preserved today? Is it possible to write about the deceased? About the living? And how should it be done?

“Kazakhstani musical heritage is preserved… somewhat. Traditional genres – ethnic and folk music – are maintained better: festivals are held, there is the Dombra Day. But Soviet pop of the 1950s-60s is almost unstudied. Names like Yeskendir Khasangaliyev or early ensembles such as Aigul and Zhetygen are barely written about. Meanwhile, Dos-Mukasan survived in public memory, partly thanks to the film, and became part of the retro canon.

Writing about the deceased is of course possible, though it is challenging – there are still relatives and loved ones you don’t want to hurt. Writing about the living is even harder – there is always a risk of breaking unspoken rules about what can or cannot be mentioned.

For me, the key is context: cultural, historical, political. I don’t like when groups call themselves ‘the first’ in a genre or in using certain instruments. In Kazakhstan, I’ve heard at least three different bands make such claims. Without understanding roots and circumstances, such statements distort the picture – and we lose an accurate view of history.”

Alexandr Deriglazov

co-founder of the Meloman and Marwin retail chains

How did people in Almaty learn about music and listen to it in the 1990s–2000s?

The 1990s were the era when culture in Kazakhstan was just beginning to open up. People searched for music almost blindly – from the first cassettes to CDs.

“We started before there were even music kiosks. We were driven by something simple: we loved music and felt we could make world culture accessible to our fellow citizens. The demand was enormous – just yesterday, much of it was forbidden, and what is forbidden is always especially attractive.”

At first, the mission was to bring as much as possible – any new album or film that had seemed unreachable just the day before. People were genuinely hungry for music.

Over time, the mission shifted from chaotic accumulation toward careful selection.

“Then there was too much content, and our role changed: we became curators. We studied global demand, neighboring markets, considered local specifics – and offered the best.”

Music was listened to in many ways: first cassettes, then CDs, later DVDs, and even vinyl, which began to grow again despite modest volumes. But most importantly, music played not only at home – Meloman stores became meeting places where people came not just to buy a disc but to talk about new releases and hear what others were listening to.

Do independent projects in Kazakhstan have a future? How should one deal with criticism?

“The world is clearly moving toward the independent and the unique – from T-shirts to music. Independent projects definitely have a future, and interest in Kazakhstan is slowly growing: our creators increasingly reach the global stage. Criticism is important – for society and for each creator. You need to listen with a cool head, understanding that there are many opinions. If you believe in your direction and have even a small group of like-minded people – keep going. You shouldn’t ignore criticism, but you shouldn’t dissolve in it either.”

Alexandr Deriglazov

co-founder of the Meloman and Marwin retail chains

How did people in Almaty learn about music and listen to it in the 1990s–2000s?

The 1990s were the era when culture in Kazakhstan was just beginning to open up. People searched for music almost blindly – from the first cassettes to CDs.

“We started before there were even music kiosks. We were driven by something simple: we loved music and felt we could make world culture accessible to our fellow citizens. The demand was enormous – just yesterday, much of it was forbidden, and what is forbidden is always especially attractive.”

At first, the mission was to bring as much as possible – any new album or film that had seemed unreachable just the day before. People were genuinely hungry for music.

Over time, the mission shifted from chaotic accumulation toward careful selection.

“Then there was too much content, and our role changed: we became curators. We studied global demand, neighboring markets, considered local specifics – and offered the best.”

Music was listened to in many ways: first cassettes, then CDs, later DVDs, and even vinyl, which began to grow again despite modest volumes. But most importantly, music played not only at home – Meloman stores became meeting places where people came not just to buy a disc but to talk about new releases and hear what others were listening to.

Do independent projects in Kazakhstan have a future? How should one deal with criticism?

“The world is clearly moving toward the independent and the unique – from T-shirts to music. Independent projects definitely have a future, and interest in Kazakhstan is slowly growing: our creators increasingly reach the global stage. Criticism is important – for society and for each creator. You need to listen with a cool head, understanding that there are many opinions. If you believe in your direction and have even a small group of like-minded people – keep going. You shouldn’t ignore criticism, but you shouldn’t dissolve in it either.”

Laura Dilmurat

PhD, author of “Contemporary Art Exhibitions of Kazakhstan,” senior lecturer at the Kazakh National Academy of Arts named after Temirbek Zhurgenov.

What role do independent projects like 91-23 play in preserving Kazakhstan’s cultural memory?

“For me, 91-23 is not just a book – it is the living voice of those who created and continue to create independent music in Kazakhstan. It is a memory of people, their dreams, their mistakes, and their victories – the things that often remain behind the scenes. If we stop documenting music and its stories, we risk losing a part of ourselves, as if we had forgotten old photographs or letters. Music is the soul of its time, and without it, it becomes harder to understand who we are. I believe this book will serve as a beacon for those who walk their own path in culture – it will inspire, support, and remind them that being independent means being free and authentic.”

Laura Dilmurat

PhD, author of “Contemporary Art Exhibitions of Kazakhstan,” senior lecturer at the Kazakh National Academy of Arts named after Temirbek Zhurgenov.

What role do independent projects like 91-23 play in preserving Kazakhstan’s cultural memory?

“For me, 91-23 is not just a book – it is the living voice of those who created and continue to create independent music in Kazakhstan. It is a memory of people, their dreams, their mistakes, and their victories – the things that often remain behind the scenes. If we stop documenting music and its stories, we risk losing a part of ourselves, as if we had forgotten old photographs or letters. Music is the soul of its time, and without it, it becomes harder to understand who we are. I believe this book will serve as a beacon for those who walk their own path in culture – it will inspire, support, and remind them that being independent means being free and authentic.”

Anastassiya Reshetnyak

researcher, trainer, monitoring & evaluation specialist; expert consultant for the UN, OSCE, USAID, GIZ.

How can researchers anticipate potential conflicts – and what should they do if pressure arises?

“When we talk about research, ethical considerations and conflicts of interest must be addressed at the planning stage, during the development of a risk-management strategy. This is not only to ‘protect yourself’ from potential negative reactions, but primarily to ensure the legitimacy of the research results and build trust in the project.

Pressure does sometimes arise. It is important to have an internal support system within the team and to document cases of pressure so that you can seek help if necessary.”

Anastassiya Reshetnyak

researcher, trainer, monitoring & evaluation specialist; expert consultant for the UN, OSCE, USAID, GIZ.

How can researchers anticipate potential conflicts – and what should they do if pressure arises?

“When we talk about research, ethical considerations and conflicts of interest must be addressed at the planning stage, during the development of a risk-management strategy. This is not only to ‘protect yourself’ from potential negative reactions, but primarily to ensure the legitimacy of the research results and build trust in the project.

Pressure does sometimes arise. It is important to have an internal support system within the team and to document cases of pressure so that you can seek help if necessary.”

A Checklist for Future Projects

A Checklist for Future Projects

Personal experience is inspiration – but it also leaves lessons behind that can be useful to anyone. Here is a short checklist every future author may find useful:

Personal experience is inspiration – but it also leaves lessons behind that can be useful to anyone. Here is a short checklist every future author may find useful:

Before publishing a book, an author should:

Before publishing a book, an author should:

Have the text reviewed by lawyers before publication. Even a few opinions can reveal risks.

Have the text reviewed by lawyers before publication. Even a few opinions can reveal risks.

Check the methodology – how inclusive and transparent it is. Explain your choices so no one assumes somebody was excluded intentionally.

Check the methodology – how inclusive and transparent it is. Explain your choices so no one assumes somebody was excluded intentionally.

Plan an information campaign explaining how and why the project was built, and how the material was collected.

Plan an information campaign explaining how and why the project was built, and how the material was collected.

Learn from other industries – examine how researchers in adjacent fields work and borrow best practices.

Learn from other industries – examine how researchers in adjacent fields work and borrow best practices.

Document your sources – keep screenshots, audio recordings, anything that may serve as evidence in case of disputes.

Document your sources – keep screenshots, audio recordings, anything that may serve as evidence in case of disputes.

Avoid relying solely on web links – websites and domains disappear; store materials locally.

Avoid relying solely on web links – websites and domains disappear; store materials locally.

Work as a team – seek allies among researchers and cultural practitioners instead of relying only on internal industry support.

Work as a team – seek allies among researchers and cultural practitioners instead of relying only on internal industry support.

Before publishing a book, an author should:

Have the text reviewed by lawyers before publication. Even a few opinions can reveal risks.

Check the methodology – how inclusive and transparent it is. Explain your choices so no one assumes somebody was excluded intentionally.

Plan an information campaign explaining how and why the project was built, and how the material was collected.

Learn from other industries – examine how researchers in adjacent fields work and borrow best practices.

Document your sources – keep screenshots, audio recordings, anything that may serve as evidence in case of disputes.

Avoid relying solely on web links – websites and domains disappear; store materials locally.

Work as a team – seek allies among researchers and cultural practitioners instead of relying only on internal industry support.

based on the experience of 91-23)

based on the experience of 91-23)

based on the experience of 91-23)

A Message for Authors from Nargiz Shukenova

A Message for Authors from Nargiz Shukenova

“Working with memory and information will always be subjective. Memories of memories, different versions of the same story – anyone who sets out to document culture will face this. But if you love this work, if it brings you joy, helps you reconcile with your own identity, and answers your personal questions – then follow this path.

I discovered an incredible amount about my contemporaries and predecessors. I watched funny videos, reread forgotten texts – and in the end, I gained a vitality I never knew I had. This project helped me understand that culture is not about looking for someone to blame, but about creating.

Yes, we lack a strong print tradition, a stable research environment, and often we have nothing to lean on. But that is precisely why it’s important to document, preserve, and share. The more we know about ourselves, the harder it is to control us – and the harder it is to mislead us.

Don’t be afraid of criticism or failure. Some may find your texts controversial or inconvenient – what matters is that you preserve the value of human experience. Culture and art have always been about that.

And even if you encounter resistance, difficulties, or lawsuits along the way, remember this: it is better to bring an idea to life and take the risk, than never try at all. Because only this creates continuity – and only this shows that everyone’s contribution has been seen and acknowledged.”

How Did the Case End?

How Did the Case End?

After publication, the book became the subject of legal proceedings. The plaintiff argued that mentioning the titles of certain songs without naming their authors constituted a copyright violation. The case was reviewed by two court instances. Ultimately, the court ruled that the book: is not counterfeit, does not contain unlawful use of copyrighted works, and is recognized as a scholarly research work.

After publication, the book became the subject of legal proceedings. The plaintiff argued that mentioning the titles of certain songs without naming their authors constituted a copyright violation. The case was reviewed by two court instances. Ultimately, the court ruled that the book: is not counterfeit, does not contain unlawful use of copyrighted works, and is recognized as a scholarly research work.

After publication, the book became the subject of legal proceedings. The plaintiff argued that mentioning the titles of certain songs without naming their authors constituted a copyright violation. The case was reviewed by two court instances. Ultimately, the court ruled that the book: is not counterfeit, does not contain unlawful use of copyrighted works, and is recognized as a scholarly research work.

“The goal of the book was to present a complete picture of the independent music scene – its history, geography, connections, people, and cultural context. We expected that readers, after learning about an artist, would want to listen to their music – and that is exactly what happened. Visibility of heritage is what brings forgotten artists back into the cultural field and serves the interests of the entire industry.

However, the interim measures have still not been lifted: the book is formally withdrawn from circulation, and we are filing an appeal to have these measures cancelled so it can return to sale.

0:00/1:34

“The goal of the book was to present a complete picture of the independent music scene – its history, geography, connections, people, and cultural context. We expected that readers, after learning about an artist, would want to listen to their music – and that is exactly what happened. Visibility of heritage is what brings forgotten artists back into the cultural field and serves the interests of the entire industry.

What happened does not feel like a victory. We simply defended the book – and it took a great deal of time and energy: eight months of work.

I would not want this to be the last book. I see how easily private initiatives can be crushed under pressure. But working with memory is what shapes the future. We made this book because otherwise it simply would not exist.” – Nargiz Shukenova

32 Years – this is not only the historical period covered in 91–23. It is also a symbol of a completed cycle: a span of time that marks an entire era.

John Cage once said: “There is no such thing as empty space or empty time. There is always something to see, something to hear. And no matter how hard we try to create silence – we cannot.”

This is the mission of 91–23. The book was born from a desire not to leave the music of Kazakhstan in “silence,” but to fill that silence with voices, stories, and memories.

91-23 is a choice to speak.

“The goal of the book was to present a complete picture of the independent music scene – its history, geography, connections, people, and cultural context. We expected that readers, after learning about an artist, would want to listen to their music – and that is exactly what happened. Visibility of heritage is what brings forgotten artists back into the cultural field and serves the interests of the entire industry.

What happened does not feel like a victory. We simply defended the book – and it took a great deal of time and energy: eight months of work.

I would not want this to be the last book. I see how easily private initiatives can be crushed under pressure. But working with memory is what shapes the future. We made this book because otherwise it simply would not exist.” – Nargiz Shukenova

32 Years – this is not only the historical period covered in 91–23. It is also a symbol of a completed cycle: a span of time that marks an entire era.

John Cage once said: “There is no such thing as empty space or empty time. There is always something to see, something to hear. And no matter how hard we try to create silence – we cannot.”

This is the mission of 91–23. The book was born from a desire not to leave the music of Kazakhstan in “silence,” but to fill that silence with voices, stories, and memories.

91-23 is a choice to speak.

What happened does not feel like a victory. We simply defended the book – and it took a great deal of time and energy: eight months of work.

I would not want this to be the last book. I see how easily private initiatives can be crushed under pressure. But working with memory is what shapes the future. We made this book because otherwise it simply would not exist.” – Nargiz Shukenova

32 Years – this is not only the historical period covered in 91–23. It is also a symbol of a completed cycle: a span of time that marks an entire era.

John Cage once said: “There is no such thing as empty space or empty time. There is always something to see, something to hear. And no matter how hard we try to create silence – we cannot.”

This is the mission of 91–23. The book was born from a desire not to leave the music of Kazakhstan in “silence,” but to fill that silence with voices, stories, and memories.

91-23 is a choice to speak.